Norman Norell (1900-1972), long considered to be Seventh Avenue’s first ready-to-wear designer with the exacting standards of a made-to-more couturier, is very much back in the spotlight 46 years after his death. Norell: Master of American Fashion by Jeffrey Banks (Coty Award-winning designer of men’s and women’s fashion) and Doria de La Chapelle (fashion, beauty and style writer) is the first book to explore the career and creations of the fashion legend. It will accompany the Museum at FIT’s upcoming exhibition Norman Norell: Dean of American Fashion; (a title he received from The New York Times) which opens on February 8.

|

| Norman Levinson Photo: Milton H Greene |

The book details how Norman Levinson, who grew up as a sickly kid in Indiana, the son of a haberdasher Jewish father and a “clothes-nut,” Methodist mother, became the toast of fashion capital New York. He began his career designing theater costumes for a local vaudeville production later moving to New York and attending Parsons and Pratt. He found work under the tutelage of fashion entrepreneur Hattie Carnegie persuading her to take him on initially for free. Their twice yearly buying trips to Paris (from the late ’20s until 1940) resulted in his fascination with haute couture — he would take the garments apart to examine and learn their construction and precise techniques managing to “translate them into American terms.”

|

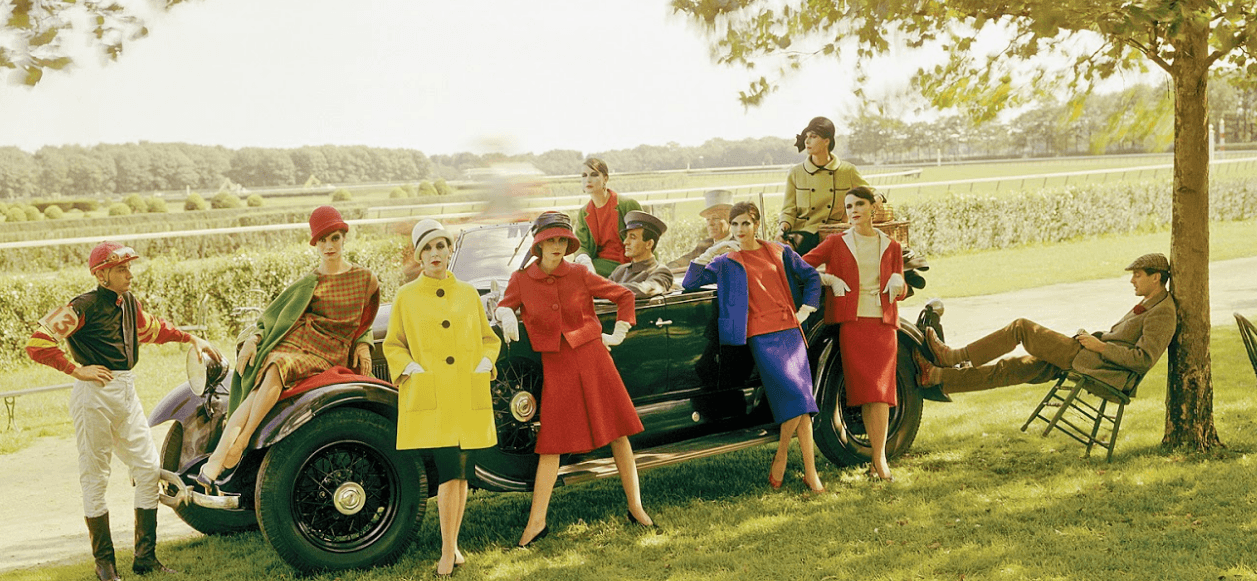

| Photo: Milton H Greene |

In 1941 after 12 years with Carmichael, Norell was asked to form a partnership with Anthony Traina, a well-respected designer of “expensive clothes for mature women who wore large sizes.” Norell agreed to a lesser salary for the privilege of having his name used and for the opportunity to design for smaller sizes. From the first season the collection was a smash hit with veteran fashion editor Carrie Donovan proclaiming “The best made merchandise in the world is Traina-Norell.” After a year with Traina, Norell hired famed fashion publicist Eleanor Lambert receiving the very first Coty Award in 1943 with several more to follow in later years. He supplied wardrobe beginning with silent film stars and later to many well-known actresses of the day such as Ava Gardner, Doris Day and Judy Garland. In 1957’s “Sweet Smell of Success”, Burt Lancaster says about an aspiring starlet, “the brains may be Jersey City, but the clothes are Traina-Norell!”

|

| Photo: Marc Fowler |

Finally in 1959 Norell opened his own label with a glamorous showroom at the prestigious address of 550 Seventh Avenue. There he held black tie evening fashion shows to the delight of his well-heeled and celebrity clients (Lauren Bacall, Babe Paley, Gloria Guinness, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Marilyn Monroe, Dinah Shore and Lady Bird Johnson were among his followers) where even the photographers covering the event dressed up. Norell enjoyed many firsts in the fashion industry: the first American designer to have his own label, the first to launch his own fragrance with Revlon in 1968 and “the first whose quality was truly on par with Paris couture.” Amazingly, he had earned the respect of Paris fashion — now they looked to him for ideas.

|

| Photo: Marc Fowler |

I enjoyed the anecdote about how Norell was the first to introduce a new style of freeing and popular culotte suits. In a rare bid to preserve order and prevent bad industry knockoffs he actually gave out the working pattern to the trade! Other signature looks from his collections included simple, elegant day wear in the form of A-line chemises often with a perfectly cut dolman sleeve, shirtwaist dresses, tailored coats, suits and dresses often with a menswear influence, sailor dresses, LBD’s — however his evening wear celebrated the elaborate including the famous fully sequined Mermaid gowns, fantasy evening coats of hand created silk or satin flowers and coq feathers, cocktail dresses of bugle beads, and chiffon, many featuring satin bows at the waist.

If you are a Norell novice, as am I, this book is a treat with photos of the clothing on mannequins and models, as well as his famous clientele; sketches by Norell and fashion illustrator Michael Vollbracht, editorials that appeared in Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar shot by top fashion photographers, and some black-and-white shots of the master in his atelier doing fittings and readying his models for the runway. The book is in sections beginning with a foreword entitled “A Red Wool Bound Buttonhole on a Black Wood Coat,” by another American couturier, namely Ralph Rucci. He extols the elevated technique and craftsmanship in Norell’s clothing — the technical aspect of Norell’s craft for the average non-couture educated reader. This theme is reprised in a later section (The Clothes) in still greater detail so that we understand — the fabrics Norell selected are of the finest quality, each article of clothing is beautifully executed with wide weighted seams, exquisite interlinings, hand sewn sequins, princess seams rather than bust darts (which he thought the mark of “home sewers”), making it remarkable on the inside as well as the outside. Other sections include The History, The Leading Ladies and The Legacy, and an afterword by bridal wear designer and Norell collector Kenneth Pool.

|

| Photo: Ernest Schmatolla |

Interestingly with all of Norell’s fashion success and business acumen, he did not become financially whole until, at 68, with the launch of his now iconic fragrance, he was able to buy out all of his investors. The book does not delve too deeply into his personal life although it does mention his failed romantic relationship with designer John Moore as well as his love of collecting “rare and beautiful things” from auction houses including a “lacquered Coromandel screen, Baccarat crystal chandeliers, fine Aubusson rugs, and fine Chinese porcelains.” A photo of the designer at home in his New York apartment looking like a “country squire” surrounded by “light-hearted slipcovers and draperies for summer” as well as one with a model wearing “slinky, silver sequined pajamas” posing in front of an ornate gilt mirror and marble fireplace give the reader some sense of how he lived — his home was a refuge from the chaos of constant production.

|

| Photo: Marc Fowler |

In the early ’70’s, after Norell had won countless accolades and awards, Ann Keaghy, chairwoman of the Fashion Design Department at Parsons (where Norell had taught and mentored students for 20 years), decided to launch a retrospective of his work from the 1930’s to the present selecting from over 1,000 pieces sourced from his loyal clients all over the country. These items along with shoes and accessories which Norell himself supplied, were to be exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum. Everything was in mint condition — devotees of the line remarked that the clothing doesn’t show age or wear whatsoever though they had been used often and over decades — many had stored their Norell treasures carefully in tissue like “sacred objects.” Tragically, the day before the exhibition was to open, Norell suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and passed away ten days later without ever having seen the tribute for himself. At his funeral (held the same day as baseball player Jackie Robinson’s), Norell’s head tailor Carmello Cardello said “You didn’t have to put a label on them; people recognized his clothes.” Now, nearly five decades later they’re still unmistakable.

Interesting and amazing how your post is! It Is Useful and helpful for me That I like it very much, and I am looking forward to Hearing from your next..

Buy Maison Margiela