As they say, the only things that are certain in life are death and taxes. But I can add one more to that: the fashion world’s ongoing obsession with black; and its popularity with women, across the board. This is quite understandable given its universal appeal. It is practical and easy to take care of (well, most of the time anyway); instantly chic, slimming, and lengthening; a perfect foil for experimental shapes and silhouettes as it is inherently restrained and chic. You feel safe in black because it can make you blend in anonymously, or it can be statement making and unforgettable. Actually, it can be anything you want it to be: edgy or conservative, rebellious or mainstream, minimal or maximal, decorative or elaborate, festive or solemn.

Speaking of solemn, yes, black is the color that has come to symbolize mourning and death. The mourning industry came into its own in the mid 1800’s, and, hard as it might be to imagine now, there was a time when, if you wore black when not in mourning, you might evoke reprobation, and risk being “classified as a dangerously eccentric woman” (as decreed by Harper’s Bazaar, August 9, 1879). This was just one of the many interesting snippets of information, I learned during the course of the morning preview of “Death Becomes Her: A Century of Mourning Attire,” the fall Costume Institute (or should I say, the Anna Wintour Costume Center) exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. It’s their first fall exhibition in 7 years and Nancy Chilton, head of communications for the Costume Institute, noted it was also their most “mellow” morning preview. Also, from my point of view, perhaps because the Met is now open on Mondays, instead of feeling like I was almost all alone as I walked inside the Great Hall (there’s nothing like feeling you have the museum all to yourself), I was surrounded by hordes of tourists and guests, so it felt a little less rarified.

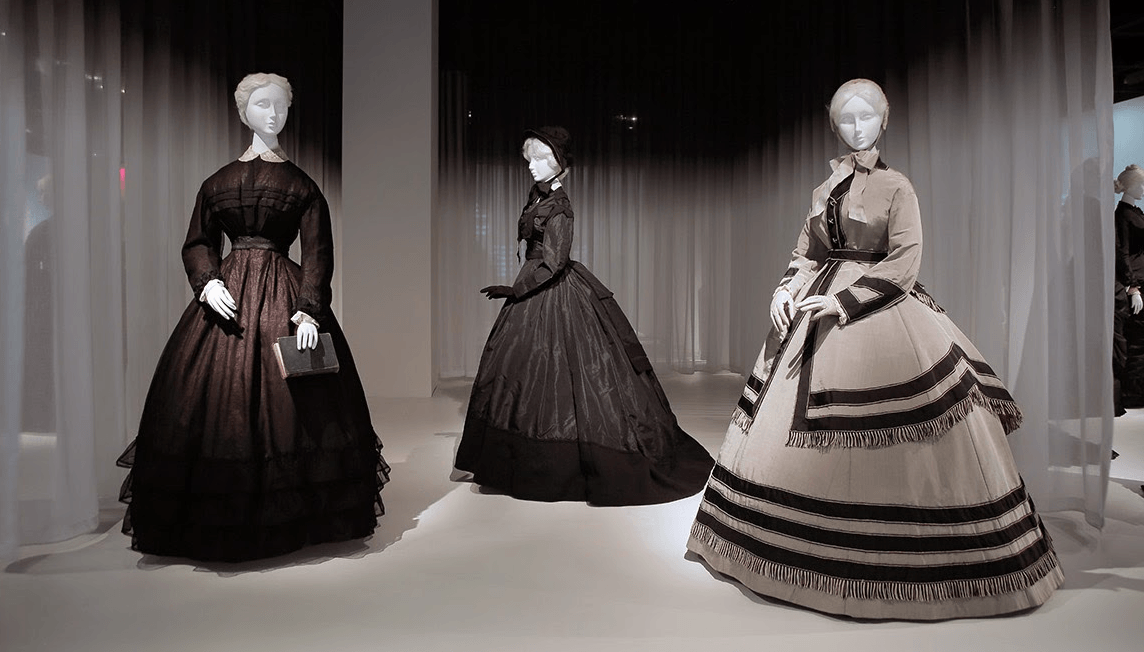

In any event, the exhibit is curated by assistant curator Jessica Regan and curator in charge Harold Koda, who admitted his favorite group are the pieces from the 1860’s, and noted that the exhibition is all about showing “respect for the deceased” through the distinctly defined fashion (which evolved through the years) as it pertained to various stages of grief. There are 30 antique ensembles (mourning dresses, mourning coats, mourning suits), and they are mostly for women (there are two ensembles for men and one child’s dress). Included is a black silk taffeta dress that was worn by Queen Victoria, and a bespoke mourning coat made of lace, knotted fringe, and silk bengaline, by the House of Worth, dated 1907. Needless to say, almost everything, including accessories (necklaces, hats, fans, parasols) is black, juxtaposed against a white backdrop, with the strains of Gabriel Faure’s haunting Requiem in D minor in the background (appropriately, this iconic piece is the Roman Catholic Mass for the Dead).

Notable exceptions to the all noir landscape are an American wedding ensemble in gray, black, and white (worn to honor of those who died during the Civil War), a duo of French sequined tulle gowns (1902), one in mauve no less, and an American mourning dress (1872 – 1874) which makes liberal use of decorative black and white silk fringe. They exemplify the dramatic shift from the sober mourning attire of Queen Victoria, and the eventual loosening of the rigid rules (even the notion that certain shiny fabrics were not appropriate began to change later as well), and they serve to illustrate the idea that certain designs could be deemed appropriate for “half mourning” or periods of “lighter mourning” (which came towards the end of the grieving cycle). The gradual blurring of the lines between mourning and fashion was exemplified by two black silk faille American mourning dresses from 1876.

And by the way, even in cases of unrelieved black, there could be many subtle and not so subtle differences. For example, while exaggerated bustle shapes were the order of the day (and they were there on display), that was not the only silhouette, and several pieces stood out by virtue of the fact that they were relatively streamlined by comparison. Along those same lines, two American mourning dresses were displayed side by side: from a distance they might look almost identical but upon inspection, it was easy to see that one defined “nun like simplicity” and the other had “decorative flourishes” made possible by intricately pleated swags along the sash and elaborate hem embellishments. Proof that even in mourning, one could still follow the dictums of fashion at the time.

|

| Cocktail party |

Later that day, I came back for the evening cocktail party during which time guests, including Yeohlee, Fern Mallis, Amy Fine Collins, R. Couri Hay, Lynn Yeager, and Jennifer Creel, got to take in the exhibit and gather in the beautiful Temple of Dendur for refreshments. While the tone and mood (and clothes) of the exhibition may be unapologetically somber and black, and there were many guests who dressed accordingly (some in the morning went as far as to wear black veils along with their Victorian hats), there were a few who refused to go with the flow. And what better way to do that than by wearing something in a bright and lively floral print?

|

| Amy Fine Collins and Jennifer Creel (photo: Marilyn Kirschner) |

While the runways for spring 2015 were filled with florals in every imaginable incarnation, the surprise has been their sighting on many stylish women right now, as we head into the winter months. And so, there was Jennifer Creel in a fur trimmed floral zip up parka, and Lynn Yaeger in Comme des Garcons. As for moi, I went with a vintage 50’s black wool Lilli Ann coat whose amazing shape recalled Victoriana, and accessorized with my Celine brass belt for a bit of shine, and what else- a touch of ‘Black’ Comme des Garcons Eau de Parfum.

And finally, I was saddened about the passing of Oscar de la Renta at the age of 82. Oscar, who I first met some 40 years ago when I was his editor at Harper’s Bazaar, was the personification of elegance and class. Always debonair and perfectly turned out, he lived life with passion, and he always had a smile on his face and a twinkle in his eyes. He carried himself with dignity at every stage of his life and did not have an un-chic, un-elegant bone in his body. The same could be said about his designs, which were the definition of timeless, feminine elegance. He had amazing longevity in an industry where that is almost impossible to achieve, and he managed to remain current and relevant by staying true to himself (to the delight of his loyal customers), without ever sacrificing his design principles.

fashion personalities). I mean, really, who else could make perfect clothes for

the likes of Barbara Walters, Laura Bush, Hilary Clinton, Michele Obama, Oprah,

and Sarah Jessica Parker? And how fitting is it that his last collaboration was

the beautiful wedding dress worn by Amal Alamuddin for her high profile wedding

to George Clooney? In one of Oscar’s last interviews on television, he told a

reporter that he did not know how long he had, but he loved life and intended to

live each day to the fullest.