|

| Andy Warhol Click images for full-size views Photos of artwork by Laurel Marcus |

“There’s the Andy Warhol you know and the Andy Warhol you don’t know,” explained our tour guide Christie Mitchell, Curatorial Assistant to Donna De Salvo at The Whitney Museum. “Andy Warhol — From A to B and Back Again” (opening on Monday through March 31) gives you the dichotomy of the public as well as the private. It’s the first retrospective of his work since the 1989 MOMA show and also the biggest. I got an exclusive sneak peek on Friday with the aforementioned small group tour and breakfast hosted by Sotheby’s.

Warhol’s earliest works of homoerotic sketches, which he tried to get into galleries, were laughed at — everyone was very closeted about homosexuality in the late 1950’s. He found acclaim instead with his award-winning I. Miller shoe ads which once graced the walls of Serendipity III. An opposing wall holds a photo of an art display he did for the Bonwit Teller’s window.

The fifth-floor exhibition continues chronologically (this makes me very happy since it is rare these days!) with his early 1960s Campbell soup cans (first shown at the Ferus Gallery in LA in 1962) and stacked Brillo boxes. There’s an entire room of his Flowers (follow the cow wallpaper — a reproduction from the walls at The Whitney’s 1971 Warhol exhibition).

Next are his “Death and Disaster” paintings taken from newspaper headlines (Electric chairs, suicides, fatal car crashes, oh my!) and finally his more experimental in mood, subject, and tone, late 1980s works. His films are scattered throughout plus there’s a screening room as well as several TV sets playing videos on the third floor. The first floor features an entire room featuring floor to ceiling colorful portraits.

Coca-Cola (2)(1961) and Coca-Cola (3) (1962) both based on ads for the soft drink, represent an evolving stylistic difference. Abstract Expressionism was the “flavor of the week” among many pop-artists when Warhol presented his two soda bottle paintings — one in what Mitchell termed a “brushy, drippy” style versus one that was much cleaner. Inviting gallerists Ivan Karp and Irving Blum along with curator Henry Geldzahler and political filmmaker Emile de Antonio to advise him on which direction he should take with his art. It was unanimous — go for the cleaner, more machine-like version. “It’s our society, it’s who we are, it’s absolutely beautiful and naked, and you ought to destroy the first one and show the other one,” noted de Antonio. This helped Warhol link his otherwise commercial techniques of reproducing using Xerox or thermo fax machines into his fine art.

Moving into photo silkscreens — perhaps what we know best about Andy — are photos of celebrities recently in the news. Here is “Gold Marilyn,” and “Silver Liz” — Marilyn had just committed suicide while Liz Taylor was having widely reported health and marital problems. “He wanted to make a painterly effect playing up the (ink) clogs in the silkscreen,” Mitchell said indicating the repeating images of “Marilyn Monroe, Andy Warhol, 1962.” A few feet away is a sculpture representing “Sleep,” a painting on glass which is a still from Warhol’s five-and-a-half hour long film of a guy literally just sleeping.

Newspaper or wire service images also inspired Warhol, particularly the gruesome ones. “He was going to do a show in Paris called “Death in America.” What does it say to reproduce images like a car crash or “Beauty of a Suicide”? He wanted to show that there was a lot of dark, not just the “pop-py”, happy 1950’s culture. His “Purple Electric Chair” was the same image from the Rosenberg execution that was happening at the exact same time. He was making a political statement in a time when he didn’t make a lot of overt political statements but would instead incorporate it in his art the way he did his gayness” said Mitchell.

In 1968 Warhol was shot by Valerie Solanas, a radical feminist and bit player in one of his films — he dies on the operating table at the hospital and is revived. “The general feeling is that post-1968 his work is not as interesting, not as innovative, not as good as before. We thought quite the opposite that it was very interesting. His 1970’s art is not brought to light as much,” said Mitchell indicating two works from right around the time he was shot — “Big Electric Chair,” 1967-68) where he has returned to his electric chair theme. This time it’s done in an optical effect of complementary colors which is foreboding and sinister.

Warhol became interested in using new materials including fluorescent and UV lights. The rolls of stacked Mylar, Untitled (1969) are a Jeff Koons-like incorporation reminiscent of Warhol’s stacked Brillo boxes.

Dominating this gallery is the oversized Chairman Mao symbolizing the US government’s entree in China. Apparently, an art dealer suggested Warhol pick a very famous subject suggesting Albert Einstein but Warhol chose Mao — using the same popularized image as in the “Little Red Book,” and on view in Tiananmen Square. Don’t miss the accompanying video from his “Factory Diaries” of Warhol painting the Mao portrait — he is racing the tape to finish before the video runs out. At one point someone asks if he’s going to silk screen it himself and he answers that it’s too big — he’ll be sending it out to be silk screened.

Themes in Warhol’s work in 1984-85 are evident from a wall of black-and-white hand-painted images not shown in his lifetime. These concern the scene on the Lower East Side where he collaborated with other artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. His mid-1980’s anxiety is represented with drawings including a “Reagan budget head,” USSR missile silos as well as veiled references to the AIDS crisis. One painting has the word Paramount on it — a reference to his boyfriend Jon Gould, vice president for corporate communications at Paramount Pictures, who died from the disease. “He was intensely anxious about AIDS washing his sheets every night. No one knew much about the disease then,” said Mitchell.

The second to last gallery contains his “Shadow” paintings. “He became obsessed with shadows. He was getting panned in reviews — he referred to his own work as a backdrop for a disco,” the curator explained. His work became more experimental using diamond dust (1979) in one painting and urine to promote oxidation in another. My favorite work is here — 1976 intensely colored “Skulls.”

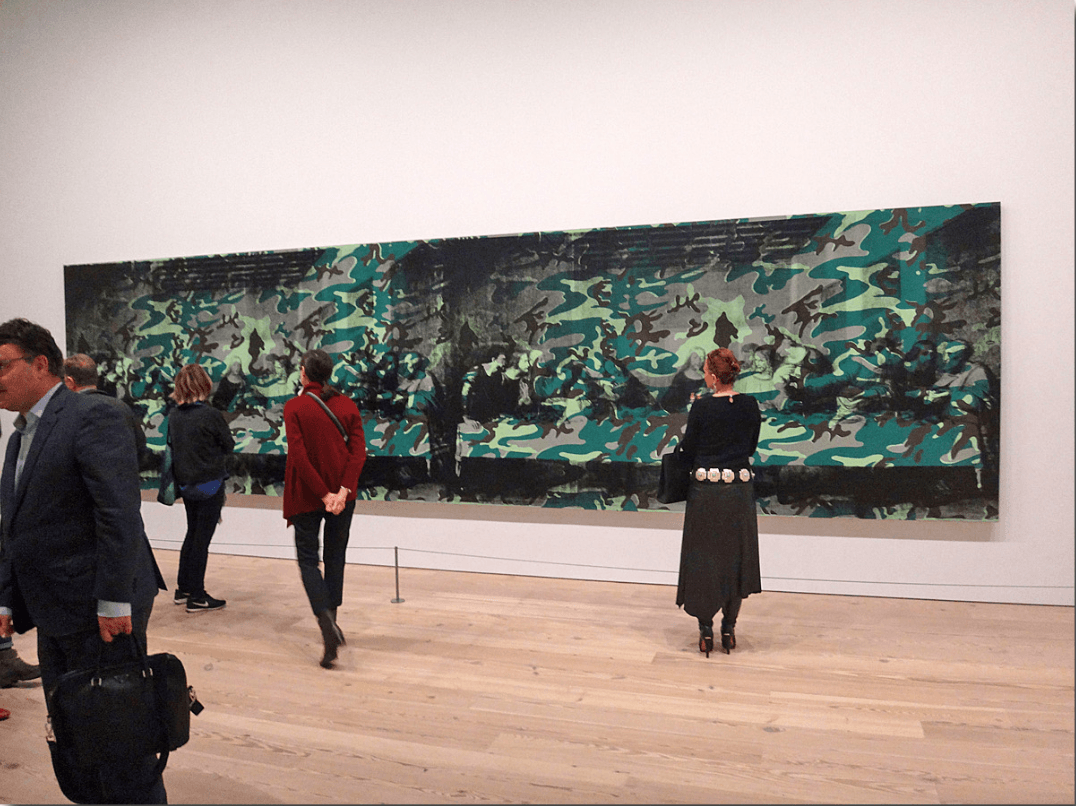

The last gallery (referred to as the “Rothko Chapel” by the curators) contains the 1986 “Camouflage Last Supper” and “White on White Mona Lisa” which revisits his previous image of Mona Lisa. In this version, she is nearly obscured by white paint.

Warhol’s giant inkblots “Rorschach,” (1984) are also here, in which he revisits a copying method of painting one side and blotting it onto the other. Most of the large and experimental paintings didn’t sell — Warhol would use the funds from his commissioned art portraits to finance the layer paintings himself.

Still, Want more? If you’d like to see or perhaps bid on Warhol’s work the Sotheby’s Contemporary art sale coming up this Wednesday and Thursday includes several good choices.

– Laurel Marcus