“The Body: Fashion and Physique” at the Museum at FIT (through May 5, 2018) examines how throughout history women’s figures figure into the prevailing fashion norms. It also demonstrates how early fashion plates, illustrations and cartoons sought to distort the body, right up to and including today’s press who often focus on mocking, stigmatizing, and body shaming women. “Fashion silhouettes change like a pendulum and the proportions change,” said Curator Emma McClendon as she pointed out a platform of various sized early stays now called corsets. “We get the idea from ‘Gone with the Wind’ that all women were cinching themselves in so tightly in order to get that 18″ waist that Scarlett complains about not being able to achieve after having children. Many women left themselves an inch or left the corsets open.”

|

| Curator Emma McClendon |

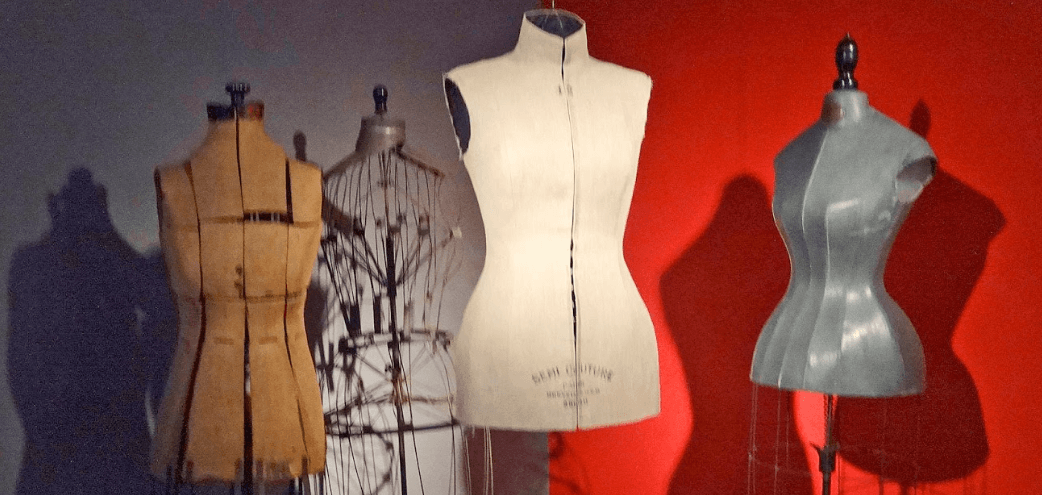

As you enter the space there are a few 18th century dress forms alongside a Martin Margiela linen tunic (1997) which mimics the dress form. This promotes the concept that the press disseminates the ideal fashionable proportion — here Margiela built his into the garment itself however there is a noticeable size differential from the earlier version. Across the aisle an opening video plays — produced by members of an advisory panel mostly composed of those involved in plus-size fashion convened for the purpose of this exhibition.

|

| Contemporary designs featuring Roberto Cavalli; LaQuan Smith; Christian Siriano; Chromat |

Designer Christian Siriano and model advocate Sara Ziff are two who are featured dropping this hot potato issue firmly in the fashion industry’s lap. Siriano who last year made a gown to fit SNL’s Leslie Jones after she groused that there were no designers willing to do so ( on display here), calls out major designers such as Gucci for not offering clothing up to size 26! (I seriously question how many women of that size would actually want to dress in Gucci, let alone how financially viable that would be). The “lack of diversity” argument on most high-end label catwalks where one only sees “thin white women” cuts to the intersectionality of size and race — a favorite cause of progressives today as well as the “food for thought” that McClendon is hoping to foster.

|

| 18th Century Proportions and Undergarments |

Back to the fashion history lesson: in the early 19th century shoulders were accentuated to minimize the waist. While corsets were once the domain of the elite they became more accessible due to the Industrial Revolution readily available through mail order in sizes up to a 36″ waist. Examples here include an example of a corset for a pregnant woman,(who didn’t go out in public at a certain point), as well as for a young girl whose version looks more like an undershirt with fastenings. Women’s bodies were thought to be weak — corsets gave them support and structure rather than being primarily for compression.

|

| Dress circa 1905 which emphasized the bust; 1910 uncorseted Liberty of London velvet dress; 1913 uncorseted Paul Poiret-style dress; early girdle with elastic sides |

By the late 1800’s, proportions of the skirt had changed to accommodate even larger crinolines making waists look small by comparison. Fullness in the back was supplied by bustles as a more voluptuous backside was in style. A medical book on display indicates that there were thought to be risks and potential health hazards to squishing internal organs and that corsets could cause scoliosis, which they actually help.

|

| Confinement gown, Corsets for Pregnant Women and Child, Bustles and Crinolines |

Going into the 20th century the corset was replaced by the girdle. These were made of elastic or rubber allowing for more flexibility and mobility while still having compression, similar to today’s waist trainers. Under the rubber girdle is a 1934 advertisement which touts the garments ability to help “melt” away unwanted fat with “a gentle massage-like-action.” A drawing entitled “Le Vrai et Le Faux Chic” (the real and the fake chic) emphasizes that only young, lean bodies could be chic; old, fat or scrawny women were portrayed as ridiculous. Fashion illustrations showing women’s heads bigger than their waists was akin to today’s Photoshop, according to McClendon.

|

| 1920’s styles and Stout Wear; rubber girdle; 1930’s silk crepe dress; House of Paquin gown c. 1935 |

By the 1920’s women led more active lifestyles — it was the age of the Suffragette with “changing expectations in the status quo,” remarked McClendon. A few plus size offerings are shown here, then known as “Stout Wear.” “These fashions obscure and negate the body. Every few decades you see plus sizes emerge such as in the ’20s and the ’80s including Vogue running a ‘Fashion Plus’ edition which was separate from its regular pages. We need to change the fashion system and continue the broadening of what we think of as the ideal body.” Yes, she actually used the word ‘broadening’ (no pun intended).

|

| Christian Dior 1951 “New Look” Ivory silk evening gown & petticoat Photo: Courtesy FIT |

Also broadening were the 1940’s shoulders in a more masculine silhouette, however one was expected to wear a compression undergarment to control “indecent” jiggle. Dior debuted the “New Look” in 1947 which really took hold by the early 1950’s. The nipped in hourglass dresses came complete with a boned understructure and tulle petticoats.

|

| 1960’s Twiggy dress; Rudi Gernreich, Halston, Danskin, and Norma Kamali |

By the 1960’s undergarments were a dirty word — Rudi Gernreich introduced the “No-Bra” Bra and compression garments were eschewed. A lifestyle change including working out and eating lighter were suggested to attain a svelte body. The 1960’s platform here features a mod floral shift look from Twiggy’s inexpensive line and a Rudi Gernreich LBD (1968) with clear plastic sides, prohibiting the use of under garments.

|

| 1980s featuring Issey Miyake; Perry Ellis; Thierry Mugler; Donna Karan, Comme des Garcons |

The 1970’s platform includes a Halston jumpsuit with totally cutout sides, as well as a Danskin unitard worn for dance and aerobics. Norma Kamali’s late ’70s jersey jumpsuit bridged active lifestyle ready-to-wear, comfort and fitness of which she is a longtime proponent. The ’80s were also about fitness as seen here in a video loop of Jane Fonda’s exercises, and Olivia Newton John’s “Let’s Get Physical.” This decade had something for everyone: both oversized silhouettes from Issey Miyake and other Japanese designers as well as a relaxed look from American designer Perry Ellis is shown alongside equally popular slim fitting garments such as Thierry Mugler’s velvet dress and experimental looks from 1990’s such as Rei Kawakubo’s famed Lumps and Bumps collection.

|

| Kate Moss and “Headless Fatty” |

The ’90s were all about grunge, and the waif-like Kate Moss was the body ideal clad in completely unstructured slip dresses. Going present day, contemporary fashions including a sheer lace “naked dress” from LaQuan Smith, worn in 2015 by a newly pregnant Kim K., demonstrating how far we have come from earlier modesty. In front of this platform an iPad illustrates how the fashion press tout their comparisons of celebrity bodies in “Who Wore It Best” (in fairness I think it’s also about how they style the looks, not just about their physique). Then there’s the popular press gimmick known as the “Headless Fatty,” which “takes away their dignity with a fat stigma,” remarks McClendon. (Actually it reminds me of a more extreme edition of Glamour’s “Don’ts”). On the wall is a video demonstrating how a model is photoshopped into having the ideal face and body.

|

| Chromat; Christian Siriano for Lane Bryant; Lucy Jones and Grace Jun |

The last platform displays a Chromat ensemble for a fuller figure with spandex and plastic boning, as well as Leslie Jones’s red Siriano custom gown and finally a few of Lucy Jones and Grace Jun designs for the disabled. While we examine what fashion imagery hath wrought as well as learn to embrace the diverse bodies and the stages that women go through as they mature, you’ll find me in the gym.

– Laurel Marcus